“Knowledge should not be sought for making money but for realising one’s ideals instead.”

In this sometimes jaded and cynical world, we would do well to revisit the philosophies of Dr Henry Hu Hung-lick. With a steadfast belief in the virtues and benefits of a good education, he dedicated his life to cultivating the talents of others less fortunate than himself. The founder of the Hong Kong Shue Yan University (formerly Shue Yan College) abided by these principles for at least 80 years until his death at the age of 105.

Dr Hu met his true match in his late wife, Principal Dr Chung Chi-yung. Both were virtuous intellectuals united by a noble desire to work for the common good of society. After their marriage, they studied overseas and learned to combine their understanding of benevolence in Confucianism with Western perspectives, emphasising both moral and intellectual education.

Born in Shaoxing, Zhejiang province in 1920, Dr Hu was adopted by his uncle after his father’s death. Although the family was poor, he was a gifted straight-A student who had already received some secondary school education before the end of his primary education, and was ranked first in the provincial examination. While still young but hard-working in the third year of secondary school, he applied to join the navy during the Japanese invasion of China in 1935 without telling his family.

Ambitions of a straight-A student

As a young man, he was ranked top in a diplomat examination in Chongqing in 1944. He met Dr Chung, who later became the first female judge in Chinese history, during his diplomatic training and the couple tied the knot the following year. Five years after the end of the Second World War, they went overseas. He took the role of Vice-Consul of the Consulate General of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic in Tashkent in 1946, and their eldest son, Yao-su, was born in the Soviet Union. He received a doctoral degree in Law from the University of Paris in 1952, qualifying as a barrister in the UK in 1954. Dr Hu began his legal practice upon his return to Hong Kong. One of ten barristers in the territory at that time, he had a particular flair for languages and was proficient in Chinese, English, French and Russian.

The couple could have led an easy, happy life within their social circle, but they chose a very different path. Dismayed by the acute shortage of tertiary education in Hong Kong, the pair gave up their stable lives and ploughed all their savings into establishing Shue Yan College in a three-storey building on Shing Woo Road, Happy Valley, in 1971. Already in their fifties, Dr Chung took on the role of Principal while Dr Hu became President, spending more than HK$500 million on Shue Yan over the years. Students would often see the principal patrol classrooms, or clean the campus herself, and she continued to oversee Shue Yan even after having a stroke. Dr Hu knew better than to argue with his formidable wife, saying: “When she’s determined to do something, nothing can stop her… There is nothing I can do. I can only try my best to work with her in this ‘doubles’ game.” Both continued to support each other until Dr Chung’s death in 2014.

Their son Hu Fai-chung, Deputy President of HKSYU, once spoke about his parents’ beliefs that “no man is born wise or learned, but they can be so through learning,” and “it takes a hundred years to educate a person and one should nurture a person with kindness”. They refused to accept the “pyramid” approach to education adopted in Hong Kong under British rule. They believed that the youth at the bottom of the pyramid being rejected from institutions of higher learning violated the principle of “education for all regardless of their backgrounds” in a civilised society. The couple strongly believed in the old Chinese saying: “An uncut gem does not sparkle” and they willingly put this into practice. HKSYU’s motto “cultivating virtues of benevolence; broadening horizon and knowledge” is taken from The Analects of Confucius.

Making demands on those in power

With much of the world now moving away from relentless activity and embracing a “lying flat” philosophy, Dr Hu’s work ethic can be seen as remarkable. A staunch believer in the old Chinese saying that “everyone bears responsibility for the prosperity of society”, he was elected as a Member of the Urban Council in 1965. Dr Hu was dedicated to tackling the problem of juvenile delinquency in Hong Kong, routinely visiting young people on the streets, squatter settlements and slums to get a better understanding of their problems. He served as Chairman of the Committee on Hawker Policy in 1968, strove to redress grievances for the unemployed and pushed for sound employment and social security systems. He entered politics and became a Member of the Legislative Council from 1976 to 1983. He championed a nine-year free education in Hong Kong during his tenure and provided free defence consultations for students arrested for participating in demonstrations. Meanwhile, he fought for permanent housing for those living in resettlement areas, and was committed to the planning of new towns. He was also the first Legco Member to visit Beijing. From 1965 to 1982, he served as a Member of the Executive Committee of the Hong Kong Housing Society.

As a barrister, Dr Hu was forthright and iron-willed, never shirking from a challenge. He advocated the enactment of a defamation law, and argued ferociously for the abolition of the concubine system. When a knight objected, saying the idea of a concubine was perfectly acceptable to himself and his elderly wife, the barrister immediately fired back, asking: “Is it humane and equal to satisfy a man’s selfish desires at the expense of a woman’s youth and happiness?” Hong Kong finally abolished the concubine system in 1971. Dr Hu’s achievements, speeches and writings carried a great deal of clout in the sector. He and Dr Chung worked together to write a book on local marriage and inheritance law, in the hope of providing protection for more people. When Dr Hu retired, the media recognised him as “a Hongkonger who made countless contributions to the city’s development”.

Giving their all to education

The path the couple chose was not an easy one. In going their own way and sticking resolutely to their principles, they faced enormous challenges while establishing Shue Yan. When the old man recalled the great hardship of founding the college in a book for HKSYU’s oral history project, he couldn’t help sighing, especially over the fight to retain the four-year college system, which lasted for three decades.

The government launched the “2-2-1 education system” in 1978. Shue Yan stuck to its educational philosophy by retaining the four-year system rather than receive government funding. Kenneth Topley, the then education secretary, warned them “to be independent is very risky” but they held steadfast. In 1988, the government changed local tertiary education to a three-year system to align with the British education system, but still they refused to waver. In 1990, nearly 1,000 students petitioned for government funding, and some even went on a hunger strike at the Star Ferry Pier. However, Dr Hu insisted on retaining a four-year system as a prerequisite for the funding, striving to defend academic freedom.

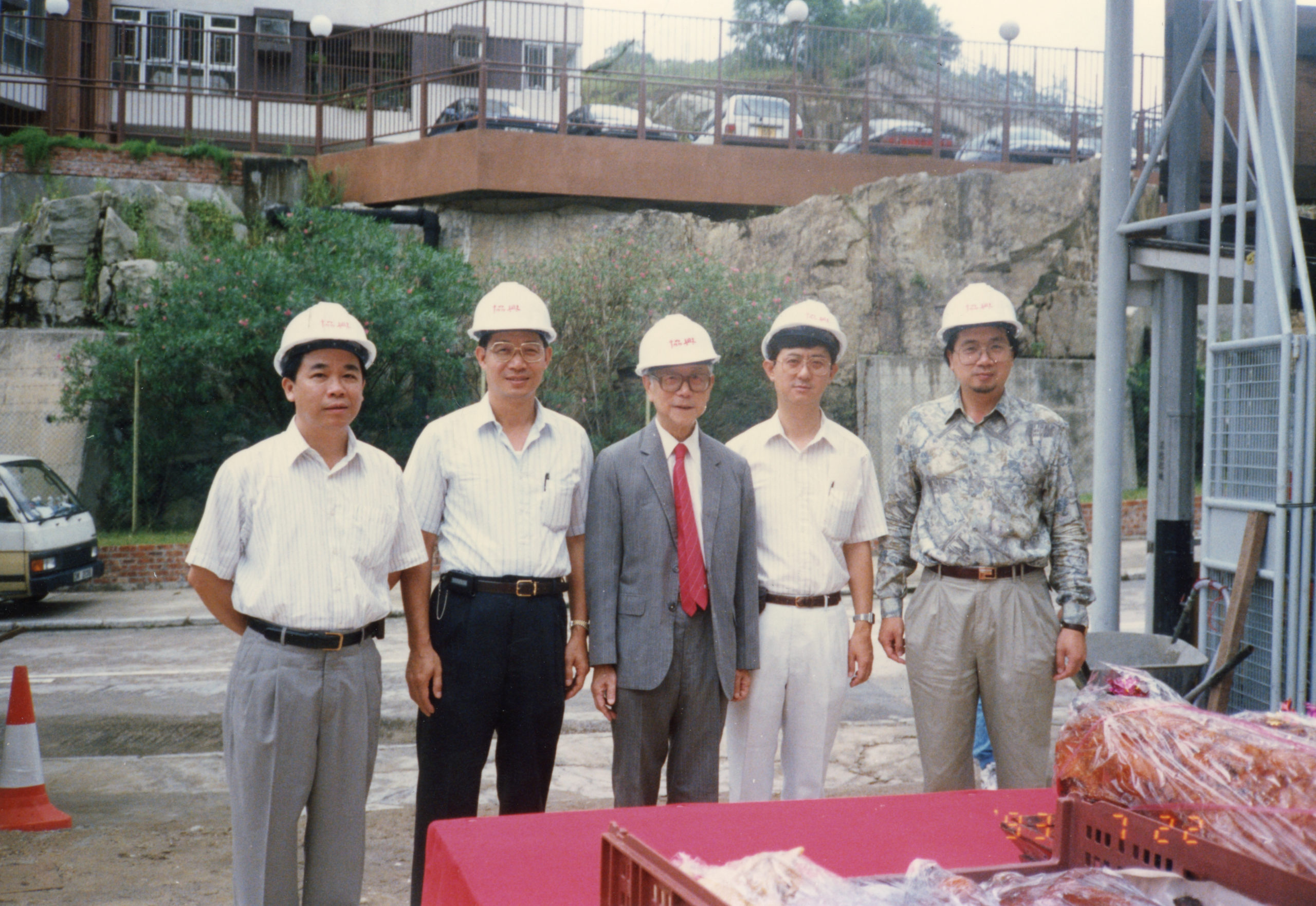

In 1983, Hong Kong was plagued by uncertainties. The Sino-British negotiations were under way, the property market was sluggish, the Hong Kong dollar exchange rate was falling and construction works were coming to a standstill. Meanwhile, a 20,000-square-metre college building on Braemar Hill was taking shape. While others might relish worldly gains, reputation and power, the couple remained true to their principles and pushed ahead with their dream. The college was built on a bumpy mid-level slope in the east of Hong Kong Island, with 176 cement pillars anchored to the rock formation to support the building. The foundation work took six years to complete. This unwavering Braemar Hill spirit still symbolises the higher education institution today. In 2006, Shue Yan finally received official government accreditation as a university. Before her death, the Principal spoke unequivocally: “I’ve completed my historic mission. I have no regrets now.”

Dr Hu was always humble and frugal. He treated staff and students like members of his extended family, frequently attending their weddings or funerals. His personal caregiver revealed that he was never comfortable spending money on himself. Even at the age of 85, he was catching the bus to work at his law firm in Central, in order to fund the college’s construction projects. He wore the same suit, and drove the same car, for decades and until recently, he was still darning his own socks.

He cut a solemn, sombre figure at the funeral of his beloved wife in 2014. Wearing a black suit, he walked weakly to the closed casket at the grave, and offered his last rose. His grief and sorrow was palpable that day as his game of “doubles” became “singles”.

The last time I saw Dr Hu, he was strolling in the gentle sunshine on Wai Tsui Crescent, Braemar Hill, with the help of a stick and a walking companion. Overlooking the city, his eyes twinkled as he recalled fond memories of his wife, along with one of his favourite phrases: “Come to terms with your fate.”

The couple lived their lives according to the adage: “Plant with your hands a thousand-year-old tree, and have a kind heart for a hundred years.” These two benevolent educators accomplished their Herculean mission, and turned into legends.

Adam Smith, Scottish philosopher and “father of economics”, famously uttered these final words: “I believe we must adjourn this meeting to another place.” Surely the couple – who gave so much and enriched the lives of so many – are now reunited in that other place, perhaps offering classes and passing on their wisdom, looking down Shue Yan from above.

By Tinny Cheng